Maltese Text-to-Speech

The first SAPI-compliant text-to-speech engine for the Maltese language, featuring three voices - male, female and child.

This project ran from September 2009 till June 2012, and was co-funded by the EU under the ERDF programme and by the Maltese Government.

More information about this project can be found on the FITA website. The Maltese text-to-speech engine is available for download from the following link.

My role in this project

I had the privilege of working on this project as part of Crimsonwing’s R&D team. Crimsonwing was awarded the contract by FITA (the Foundation for Technology Accessibility) for the development of this project. Apart from developing the speech synthesis engine, Crimsonwing also developed the iSpeakMaltese apps, which are available freely for download from the GooglePlay store (follow this link).

Published research

This project contained a heavy element of research, apart from the requirement of developing a fully-fledged functioning and real-time product. Novel aspects of this research were accepted for presentation at an academic conference and for publication in a peer-reviewed academic journal – these are listed on my publications page.

Text and Diphone Statistical Analysis

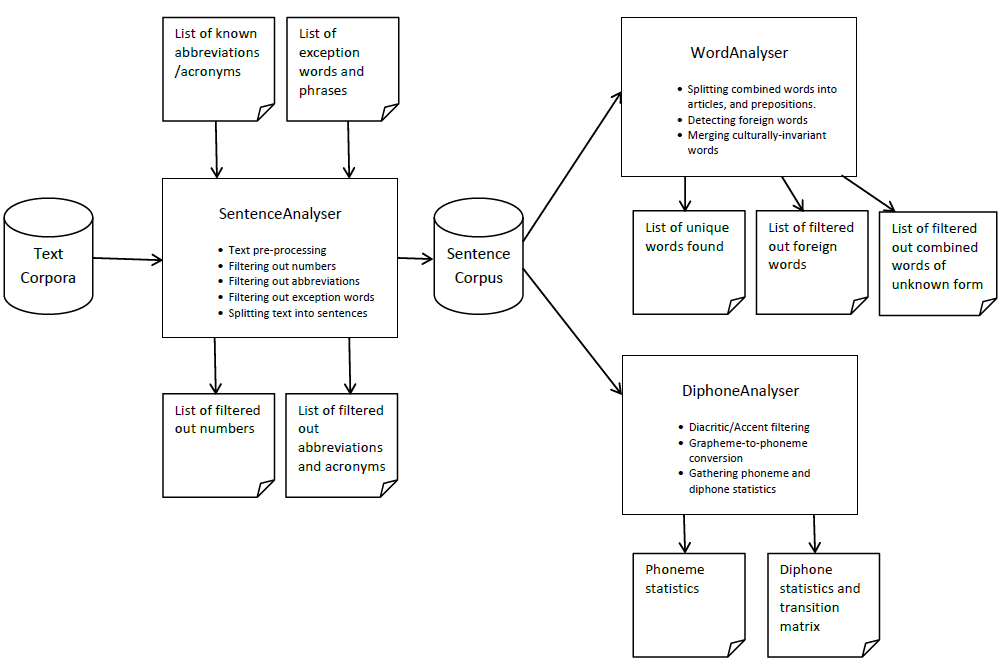

My main contribution to this project was the statistical analysis of the text corpus and that of the diphone database. This statistical analysis was necessary because of the technique chosen for speech synthesis, that of concatenative speech synthesis. By performing statistical analysis on the frequency of sound occurences in the Maltese language, we could then optimise the collection of these sounds (diphones and triphones) and ensuring that the number of recording instances of these sounds reflects their true frequency of occurence in spoken Maltese.

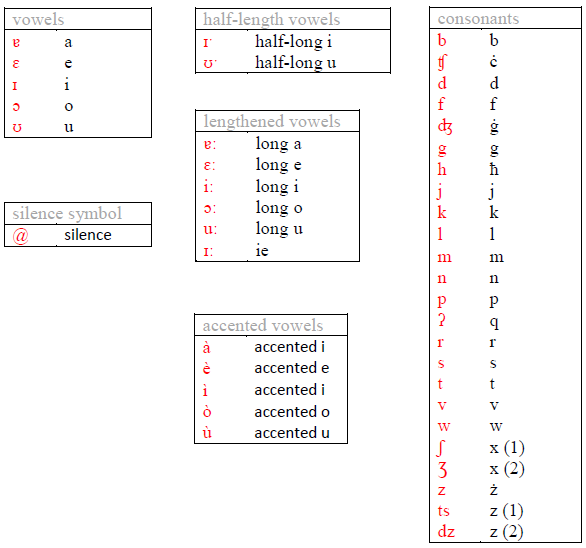

I also contributed to the development of the rule engine for performing grapheme-to-phoneme translation, i.e., converting written Maltese text to its sound representation (specified as a sequence of diphones). This is also referred to as G2P for short, or as letter-to-sound conversion.

Unlike languages like English, G2P in Maltese is quite straightforward and can be done via a sequence of context-sensitive re-write rules.

\[f_i: xGy \rightarrow xPy \; | \; \text{<conditions>} \qquad G \in \{ \text{graphemes} \}, P \in \{ \text{phonemes} \}\]Thus there is no need for complex machine learning algorithms for G2P. But then the Maltese language exhibits complexity in other areas such as linguistic morphology and verb formation, when compared to languages like English. The context-sensitive re-write rules used for performing G2P in Maltese can be found here.

Audio Signal Processing

My other main contribution to this project was in the audio post-processing stage. After speech is synthesised from a sequence of recordings of diphones, selected via the Viterbi algorithm, the concatenated sound has sound artefacts at the join positions (clicks) – these need to be eliminated in a post-processing stage. Since the speech synthesis engine is SAPI compliant, it needed to support features like varying the playback rate and sound volume adjustment.

Varying the playback rate can not be implemented as a simple compression of the audio signal, else the frequency of the sound changes as well (causing the voice to sound like that of Mickey mouse). Thus a special algorithm has to be used that varies the temporal duration while keeping the sound frequency fixed. I implemented this via the use of the WSOLA algorithm (Waveform Similarity based Overlap-Add).

Phoneme & Diphone Statistical Analysis

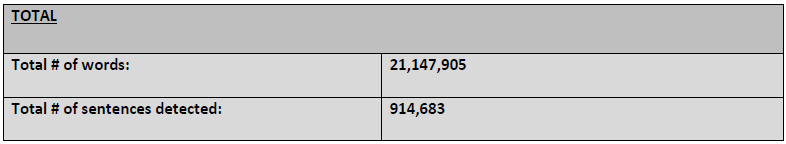

Below is some information about the text statistical analysis that was performed as part of the work for the development of the Maltese Speech Synthesis Engine.

Text Corpus Creation

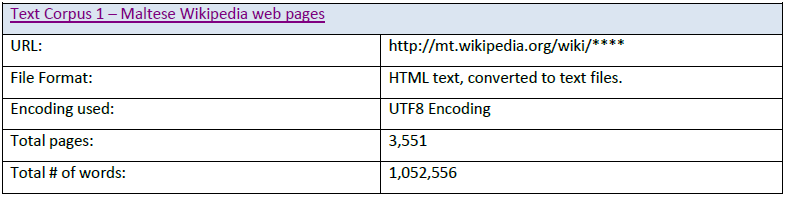

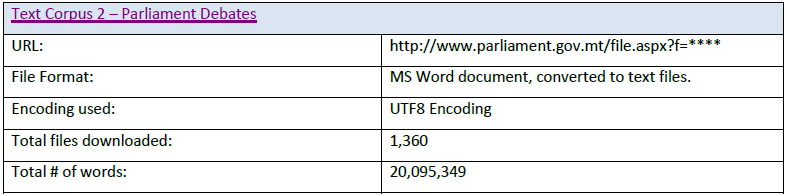

The text corpus used was scraped from the Internet using web crawling tools and converted to Unicode text.

Data Cleaning

Here is a brief description of the data cleaning tasks performed on the raw text in order to standardise it and simplify the language morphology:

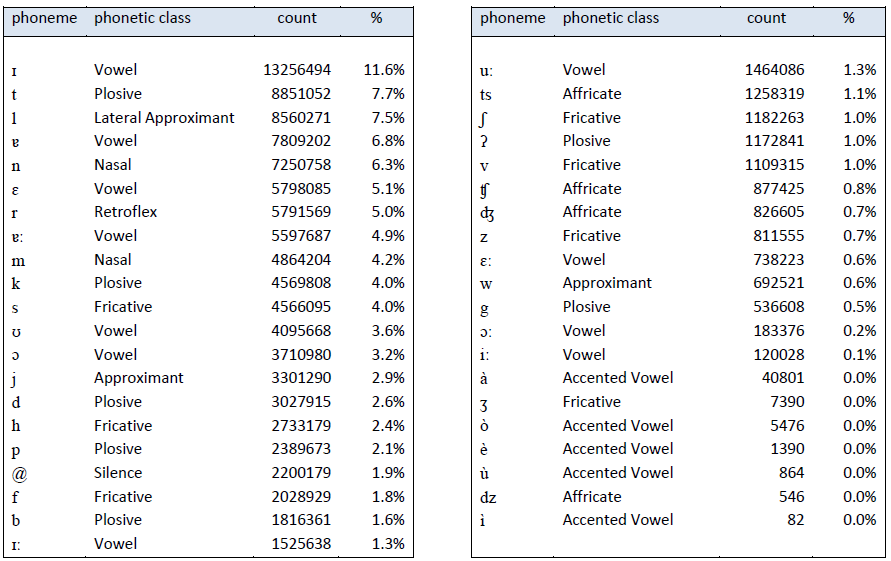

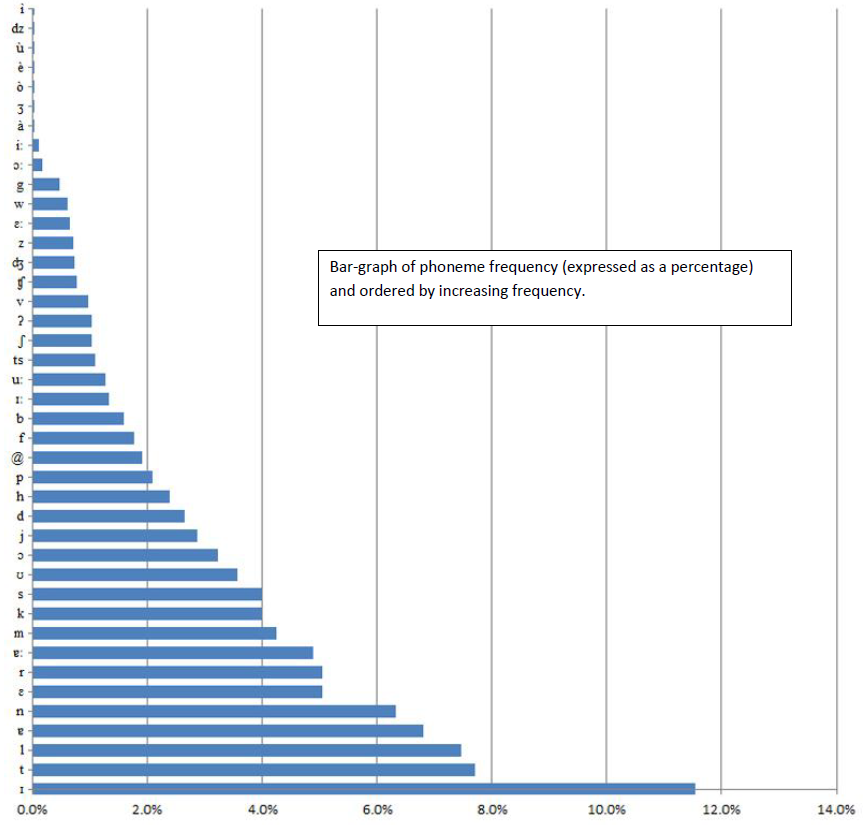

Phoneme Statistics

After performing G2P conversion, the corpus contained a total of \(114,774,451\) phonemes. Statistical frequency analysis was performed on this phoneme corpus:

Diphone Statistics

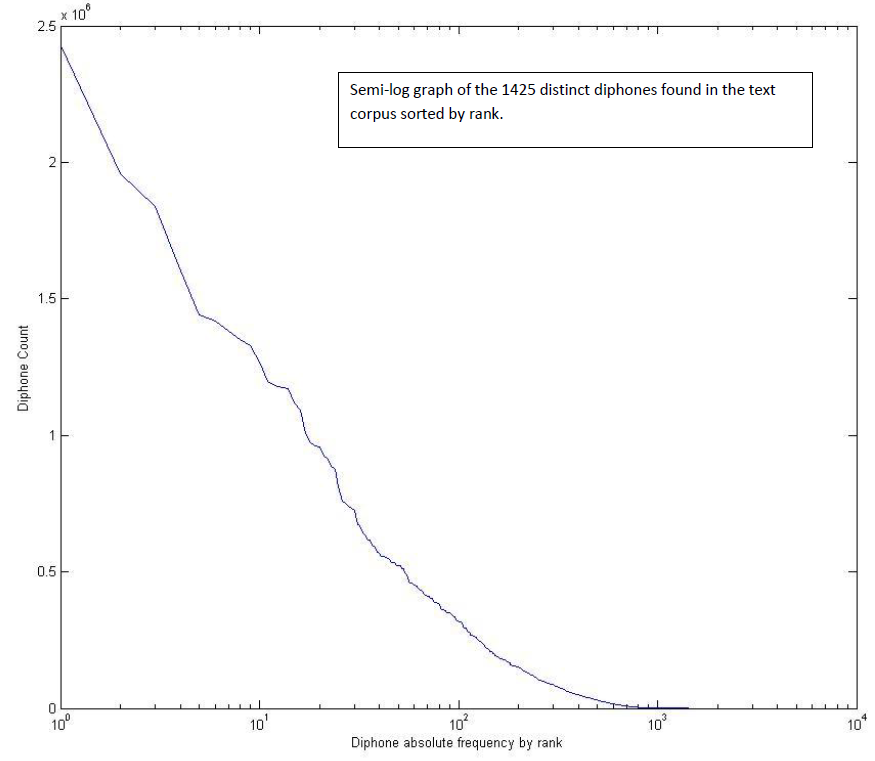

The corpus was also statistically analysed for the frequency of diphones (two consecutive phonemes). In total, there are \(113,860,068\) total diphones in the corpus.

Theoretically speaking, the maximum number of diphones (all phoneme combinations) is: \(43\) x \(43\) = \(1849\) distinct diphones. But the actual number of diphones found in the text corpus was of \(1425\), i.e. only \(77%\) of all possible combinations were found. Alternately, \(23%\) of all possible diphones didn’t occur even once amongst 113 million diphones.

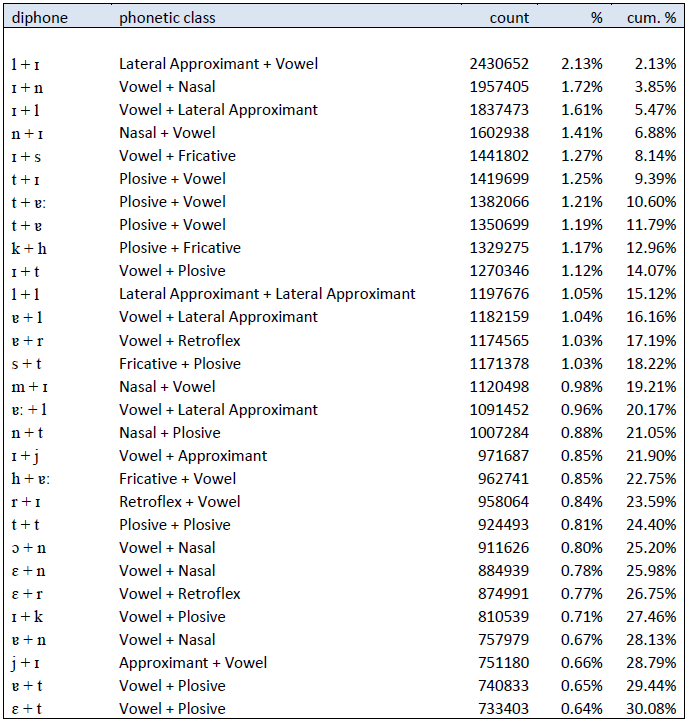

The following are some statistical results on diphones:

Of the \(1425\) distinct diphones found, the first \(347\) diphones account for \(90%\) of all diphone occurrences. And the first \(74\) diphones account for \(50%\) of all diphone occurrences; some of these are given in the table below:

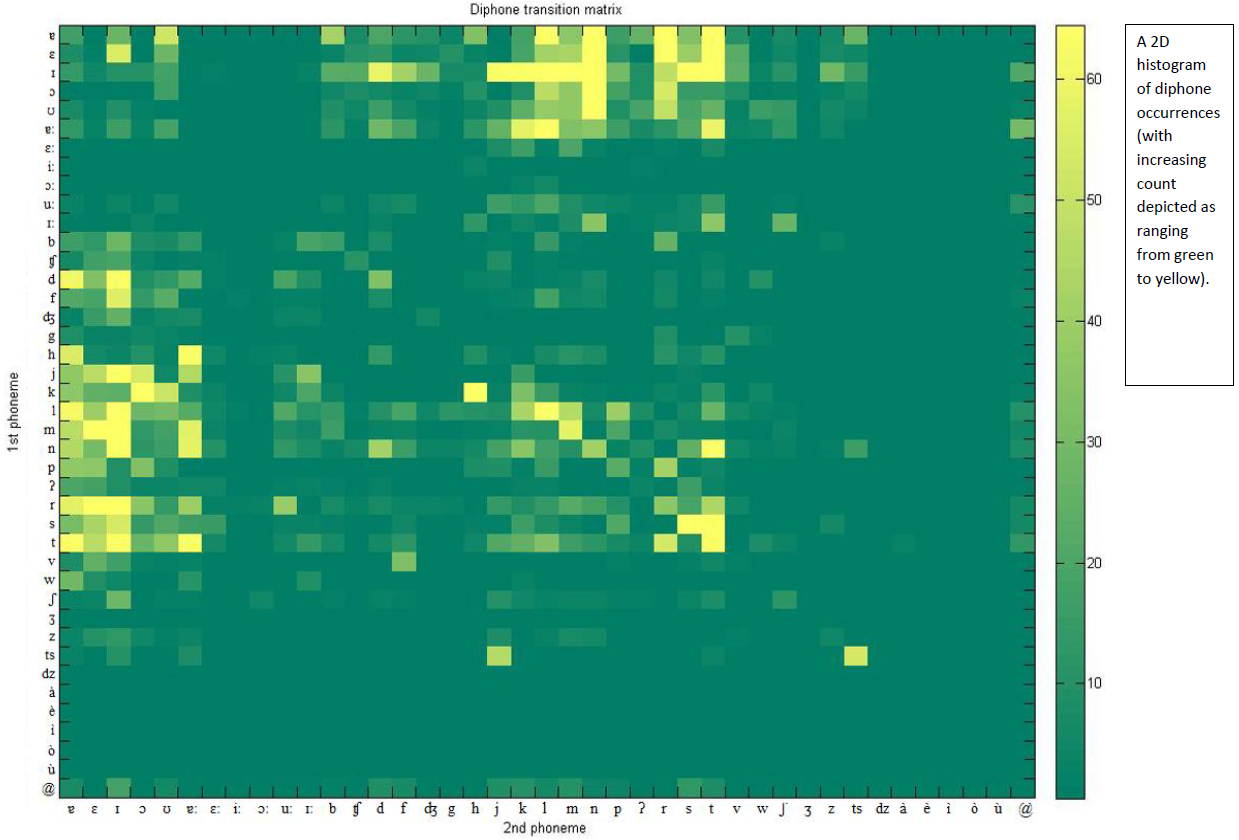

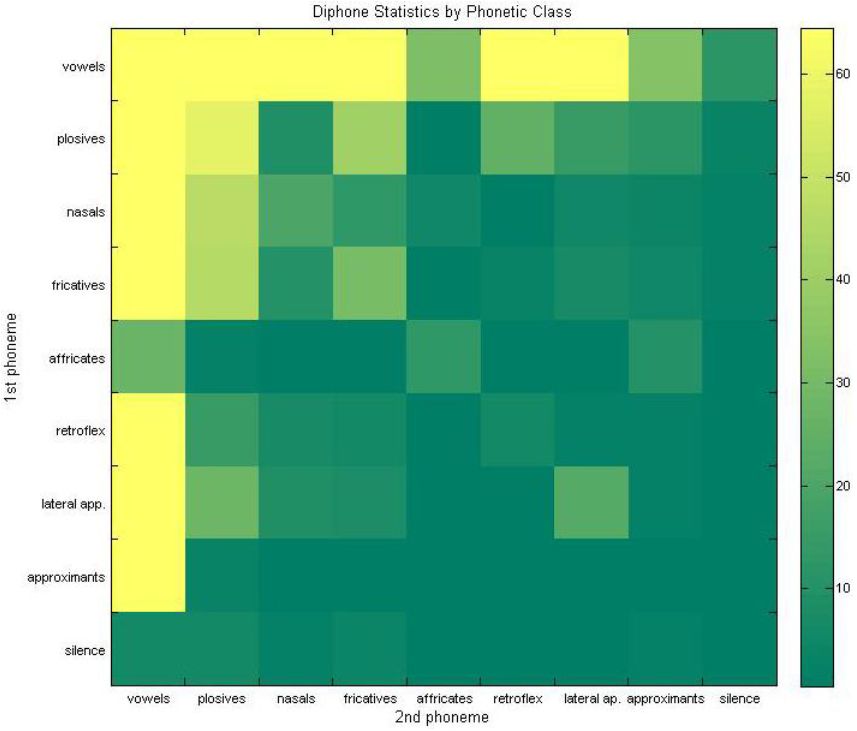

The above diphone transition matrix shows the frequency of having diphone pair \(<d_1 d_2>\). For example diphone \(< l + ɪ >\) is the most common diphone in spoken Maltese andthe transition matrix has a high value at this point. Below is another diphone transition matrix, but this time clustered by phone type.

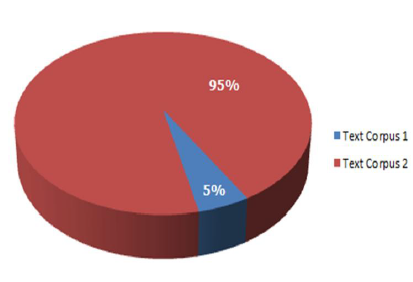

Diphone Statistics Variation between Text Corpora

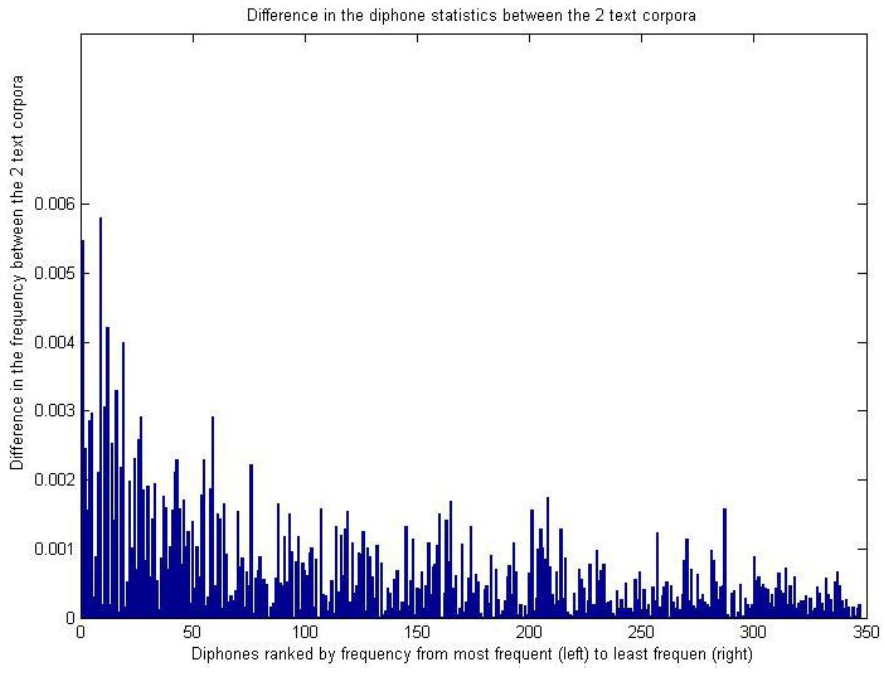

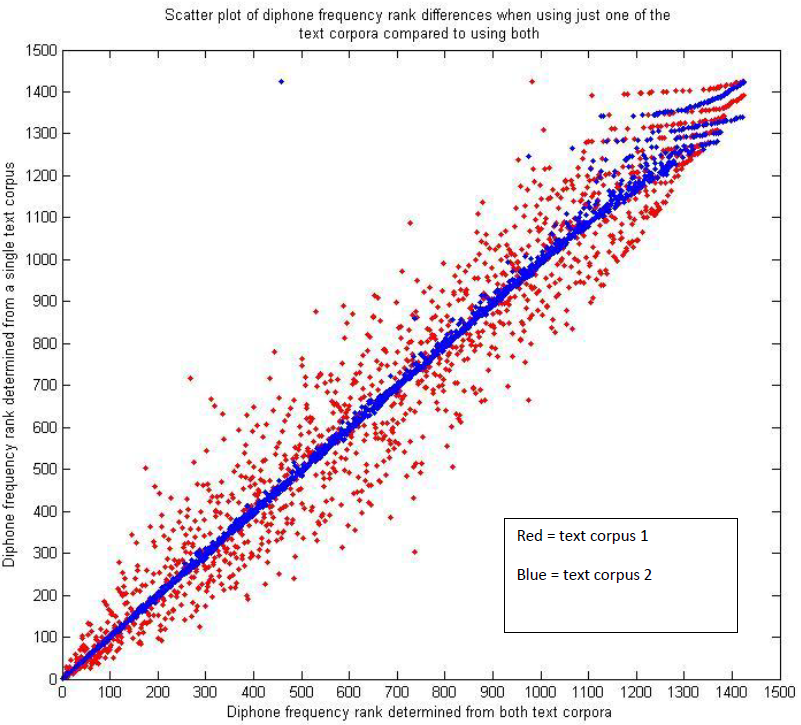

A simple analysis was performed to get an idea of how much diphone statistics can vary between different text corpora. In this case, diphone statistics were individually calculated for each of the 2 text corpora used here and normalised (to counter for the difference in sizes of the 2 text corpora). Then the differences between the diphone statistics were calculated. The following graph shows the differences for the first 347 diphones (i.e., covering 90% of all diphone occurrences).

More in-depth information about the data cleaning and statistical analysis process can be found in this document

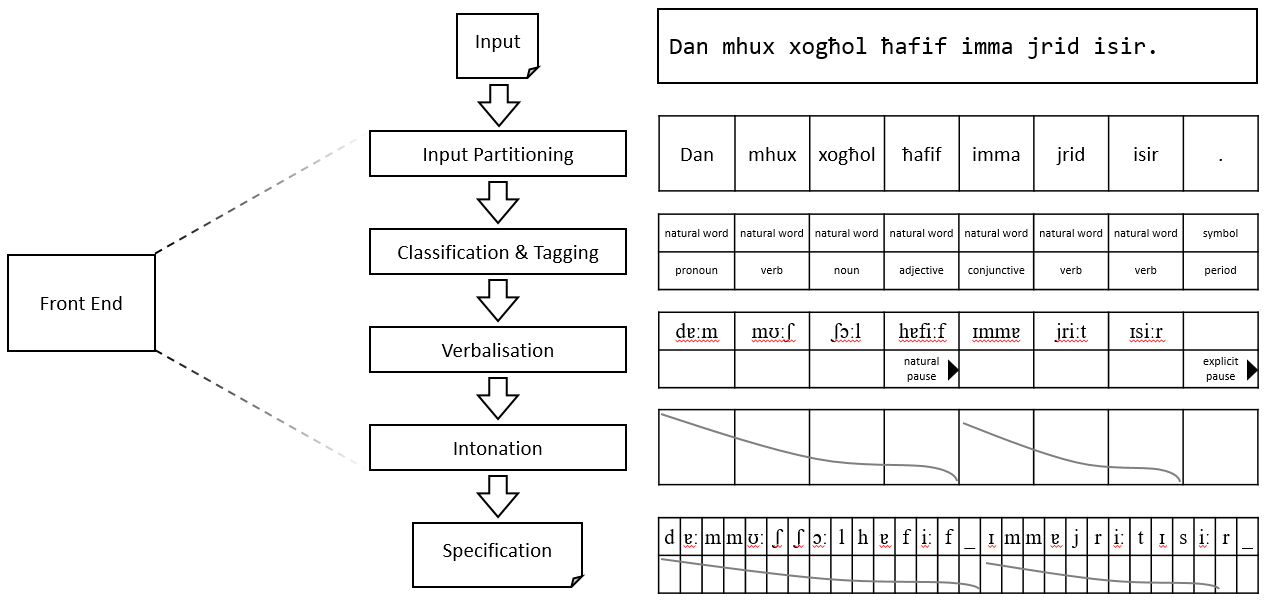

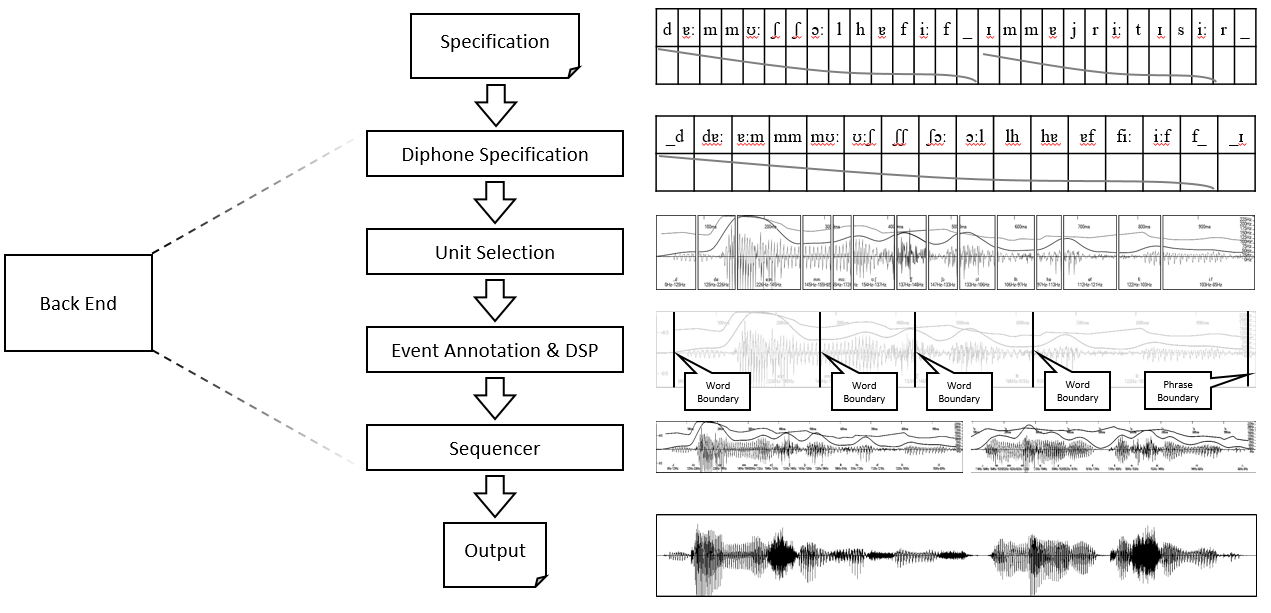

More detail on the general architecture of the speech synthesis engine can be found in this paper.

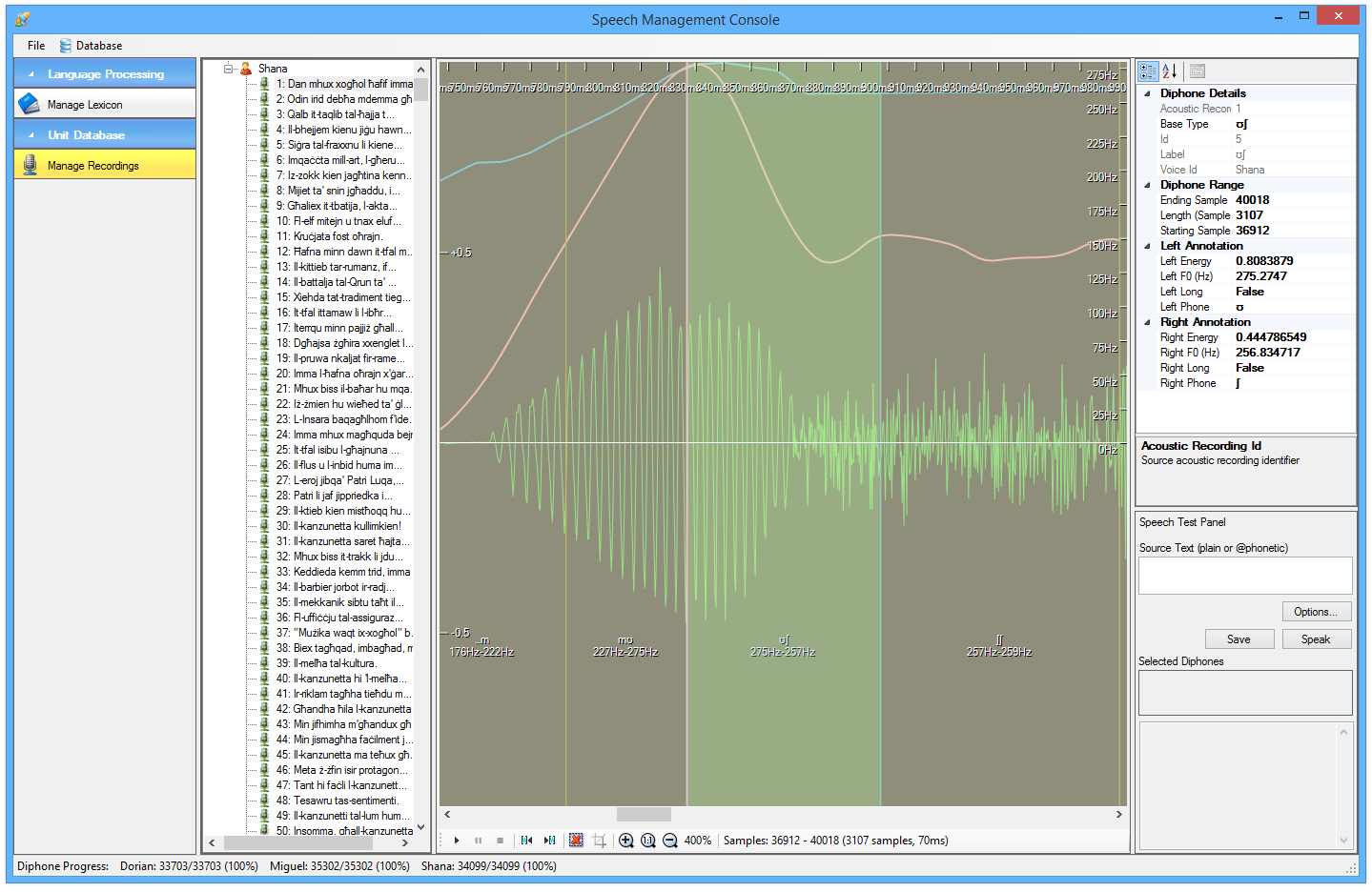

In addition to the engine and the mobile apps, a number of internal support tools were developed to help in the process of data preparation. Apart from support tools to create the lexicon (the dictionary of words with their related feature data such as part-of-speech, phonetic representation, syllabification, etc.), a number of other audio support tools were developed for cutting & preparing the diphones to be used by the engine.

Many thousands of diphones (over 100,000) had to be manually selected from the voice actor recordings and cut out and refined for use. This was a laborious & tedious process. Thus the use of tools to support & facilitate this manual process was quite important. Some screenshots of these tools are shown below: