OmniApp - Omnidirectional Visual Surveillance

This is my MSc project, titled “Omnidirectional Visual Tracking”, that was submitted in 2003 for my MSc Engineering & Information Science degree at the University of Reading.

The source code, which is available on github here, is in C++.

The dataset used for training and testing the algorithms is the PETS 2001 dataset that is available for download here. The version acquired using the catadioptric sensor is used.

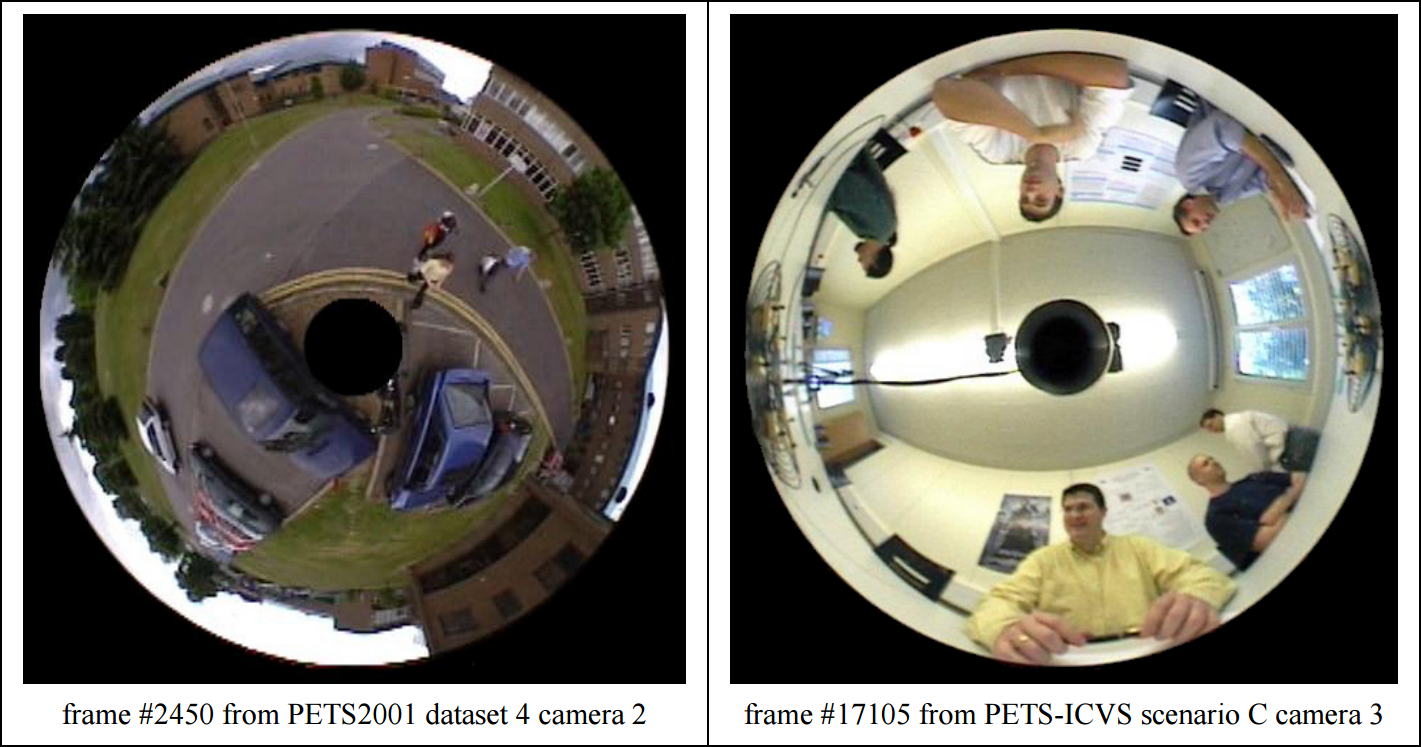

Below are two sample frames of the PETS 2001 video sequences that were used as datasets for my OmniApp project.

A catadioptric sensor is a camera made up of a mirror (catoptrics) and lenses (dioptrics). By simplifying things a lot, one can think of a catadioptric sensor as consisting of a normal camera viewing the world reflected in a parabolic-shaped mirror. To be useful, the mirror must be perfectly aligned with and placed at a precise distance from the camera. The main advantage of a catadioptric sensor is its panoramic view of the world, being able to view a full hemisphere (360 degrees by 90 degrees). That’s why such catadioptric cameras are also called omnidirectional cameras — they are able to see in every direction. Some examples and applications of catadioptric sensors can be found here and here.

Reproduced below is the abstract of my thesis.

ABSTRACT

Omnidirectional vision is the ability to see in all directions at the same time. Sensors that are able to achieve omnidirectional vision offer several advantages to many areas of computer vision, such as that of tracking and surveillance. This area benefits from the unobstructed views of the surroundings acquired by these sensors and allows objects to be tracked simultaneously in different parts of the field-of-view without requiring any camera motion.

This thesis describes a system that uses an omnidirectional camera system for the purpose of detecting and tracking moving objects. We describe the methods used for detecting objects, by means of a motion detection technique, and investigate two different methods for tracking objects – a method based on tracking groups of moving pixels, commonly referred to as blob tracking methods, and a statistical colour-based method that uses a mixture model for representing the object’s colours. We evaluate these methods and show the robustness of the latter method for occlusion and other problems that are normally encountered in tracking applications.

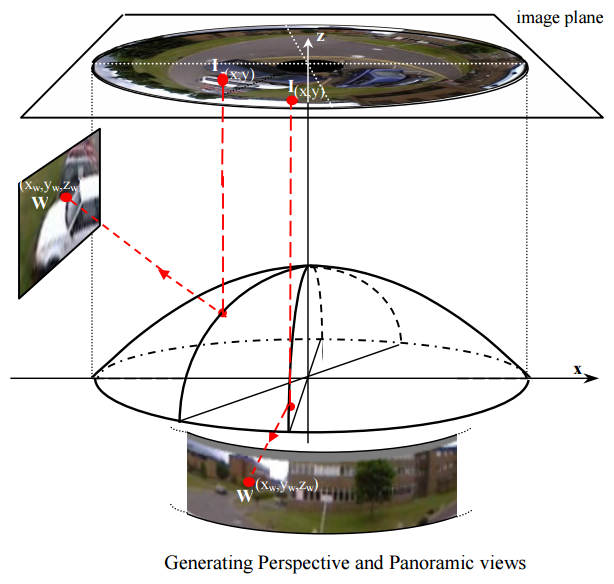

For this thesis, we make use of a catadioptric omnidirectional camera based on a paraboloidal mirror, because of its single viewpoint and its flexibility of calibration and use. We also describe the methods used to generate virtual perspective views from the non-linear omnidirectional images acquired by the catadioptric camera. This is used in combination with the tracking results to create virtual cameras that produce perspective video streams while automatically tracking objects as they move within the camera’s field-of-view.

Finally, this thesis demonstrates the advantage that an omnidirectional visual tracking system provides over limited field-of-view systems. Objects have the potential of being tracked for as long as they remain in the scene, and are not lost because they exit the field-of-view as happens for the latter systems. This should ultimately lead to a better awareness of the surrounding world – of the objects present in the scene and their behaviour.

The full MSc thesis report can be found below:

- Front matter

- Chapter 1 - Introduction

- Chapter 2 - Omnidirectional Vision

- Chapter 3 - Catadioptric Systems

- Chapter 4 - Application Scenarios

- Chapter 5 - Implementation Aspects

- Chapter 6 - Catadioptric Geometry and Virtual View Generation

- Chapter 7 - Catadioptric Camera Calibration

- Chapter 8 - Moving Object Detection

- Chapter 9 - Object Tracking - an Overview

- Chapter 10 - Blob Tracking

- Chapter 11 - Colour-based Tracking

- Chapter 12 - 3D Localisation and High-Level Processing

- Chapter 13 - Conclusions and Future Work

- Bibliography

- Appendices

A key element of my thesis was the de-warping of the omnidirectional video stream. This dewarping operation involves some complex and time-consuming mathematical operations. The mirror has a paraboloidal shape and is thus non-linear in nature. The video stream runs at 25 frames per second, thus the OmniApp program can only afford spending 40 milliseconds per video frame. The dewarping operation must consume a fraction of these 40 milliseconds in order to leave time for more interesting stuff, like motion detection and object tracking.

After a lot of tinkering and experimentation, a fast enough dewarping operation was achieved. Extensive use was made of the processor’s MMX instructions to speed up processing. MMX is a single instruction, multiple data (SIMD) capability of Pentium processors and above. In addition, many of the dewarping computations were cached into memory to avoid repeated computations.

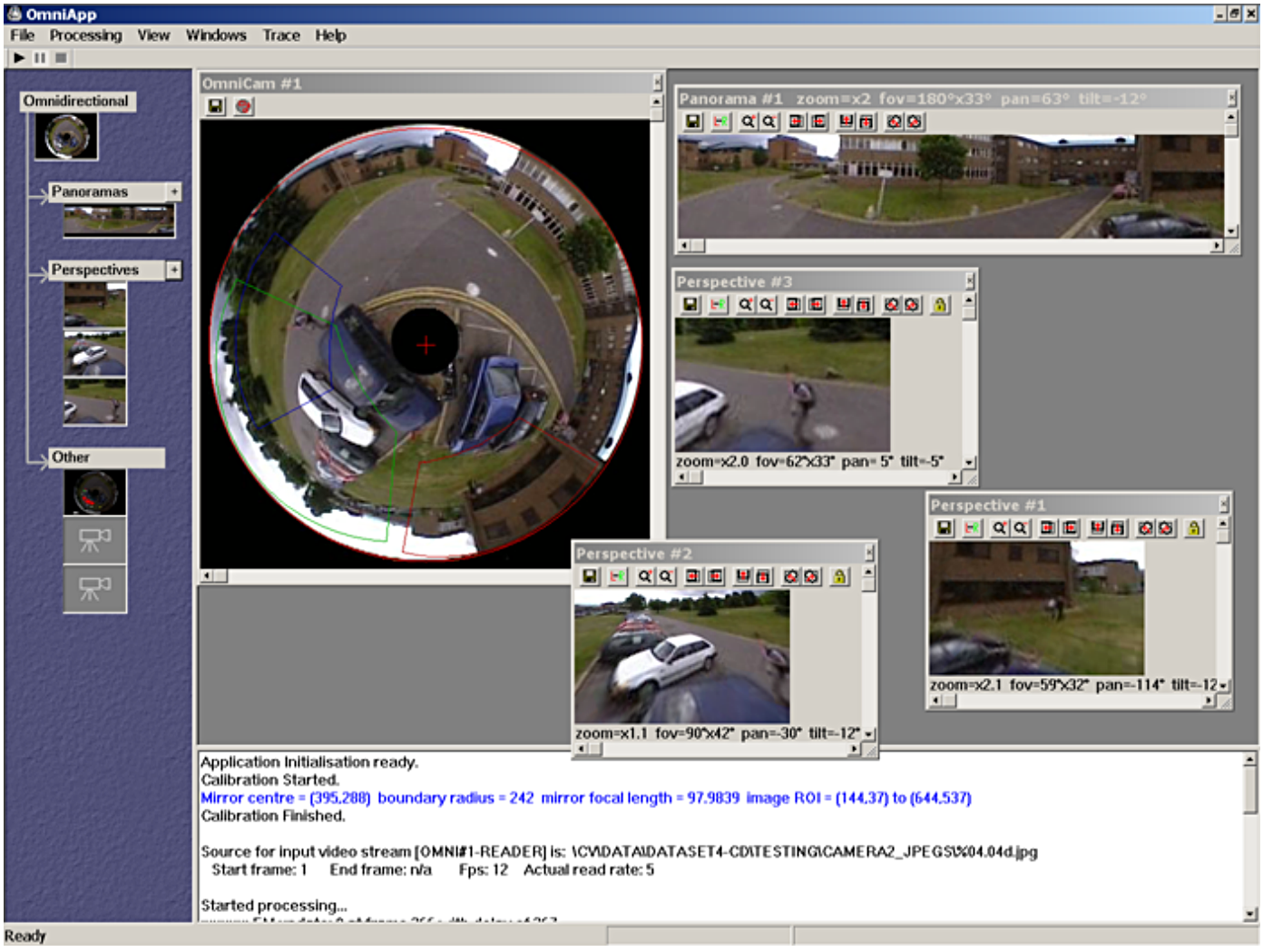

What makes omnidirectional cameras interesting is that via dewarping part of the video frame, one can simulate a normal (perspective) camera. It’s as if one has a virtual camera. What’s more, one can ‘move’ this virtual camera and make it point in any direction. This is especially useful for tracking people as they move through the scene being observed by the real omnidirectional camera. This is what my OmniApp program does. It allows you to create an unlimited number of virtual cameras. These virtual cameras can be of two types - normal 4:3 perspective cameras or panoramic cameras. An example screenshot of my program is shown below. In this case, we have 3 perspective virtual cameras and one panoramic virtual camera. These virtual cameras can be created or destroyed on the fly, while the omnidirectional video stream is being acquired live.

Each virtual camera is equipped with a toolbar to allow the user to move the camera, to zoom in or out, or to roll the camera along its central viewing axis.

A key element of my thesis was the detection and tracking of people. This allowed me to add a feature in OmniApp that I think is quite useful in visual surveillance: a virtual camera can be made to automatically follow the person as he moves through the scene. And since the number of virtual cameras is only limited by the processing available, one could create a virtual camera for each person that is present in the scene and have these virtual cameras follow each person as he/she moves along. This illustrates one of the main advantages of omnidirectional cameras when compared to more traditional pan-tilt-zoom (PTZ) cameras. A PTZ camera can be navigated to follow only one target at a time, while an omnidirectional camera sees the whole scene all the time.

In OmniApp, one can create a virtual camera and with a simple click of a button can have that camera follow a person as he walks across the scene. The zoom level of the virtual camera is also automatically adjusted to ensure that the person is clearly and fully visible within the virtual camera’s field of view. Examples of virtual cameras that are automatically tracking their targets are shown below. Part of the omnidirectional video frame is shown as a backdrop and the outline of the virtual camera’s field-of-view is drawn on the omnidirectional image (the outline is colour-coded to help identify to which virtual camera it belongs to).

Different ways of automatically tracking objects within OmniApp’s GUI:

Implementation Aspects

Something about the implementation of OmniApp. All the code is written in C++ and use is made of the library OpenCV.

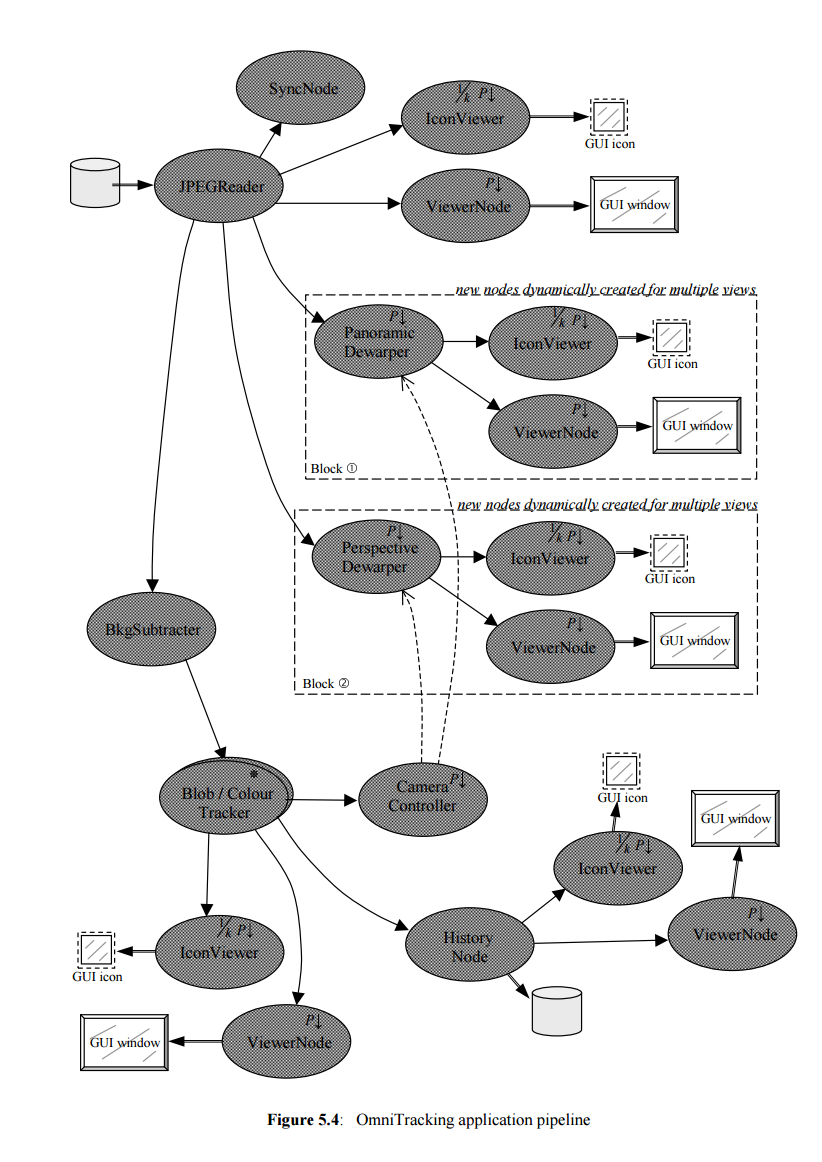

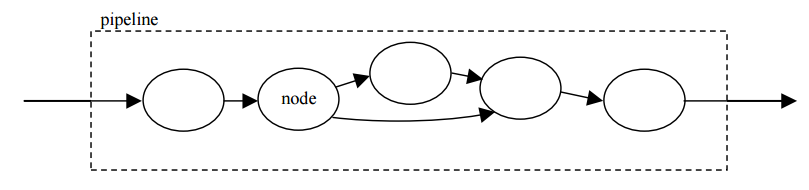

In order to support the creation of virtual cameras on the fly, heavy use is made of object orientation and polymorphism. A pipeline model is adopted for handling the processing requirements of the cameras (both real and virtual).

Processing nodes can be added to or removed from each pipeline dynamically and seamlessly while a camera is running live. For example, if the user assigns a virtual camera to track a person, then a set of new processing nodes are added dynamically to the camera’s pipeline, with one node doing the tracking of that person, another node handling the zoom adjustment of the camera, and another one rolls the camera to ensure that the person remains upright in the camera’s view. And if the user re-takes manual control of the camera, these nodes are dynamically removed from the pipeline and deleted.

Each camera’s pipeline does not operate on its own — it is embedded within the pipeline architecture of the whole OmniApp program. This ensures that all virtual cameras run in sync with each other. Another reason is to allow for communication between different virtual cameras and re-use of precious resources and computations, such as dewarping. More detail can be found in chapter 5 of my thesis report.

Computer Vision Algorithms

Something about the computer vision techniques and algorithms used in OmniApp. The technique of Background Subtraction is used to perform motion detection. Very briefly, this technique automatically learns what the empty scene (a scene without people in it) should look like. This knowledge is referred to as the background model. Then, equipped with this background model, the algorithm is able to tell if something new (hopefully a person) has entered the scene or not. The tricky part is that the background model can quickly get out of date and needs to be mantained and updated all the time. For example, when the sun goes behind a cloud the scene (the background) changes drastically. More detail can be found in chapter 8.

For the tracking of objects, a colour-based technique is used. First, we make use of spatial proximity when tracking people. A person does not move much from one frame to the next — so we can safely assume that a person visible in one frame is the same person that is viewed in the next video frame but slightly to the left or right. In addition, colour can be a useful discriminating factor — there is a good probability that two persons moving close to each other will have different coloured clothes. This can be especially useful when one object occludes (hides) another.

In the sequence of images below, the person with the yellow top passes behind a seated person (with dark top). Colour allows us to distinguish the two persons and to track them successfully.

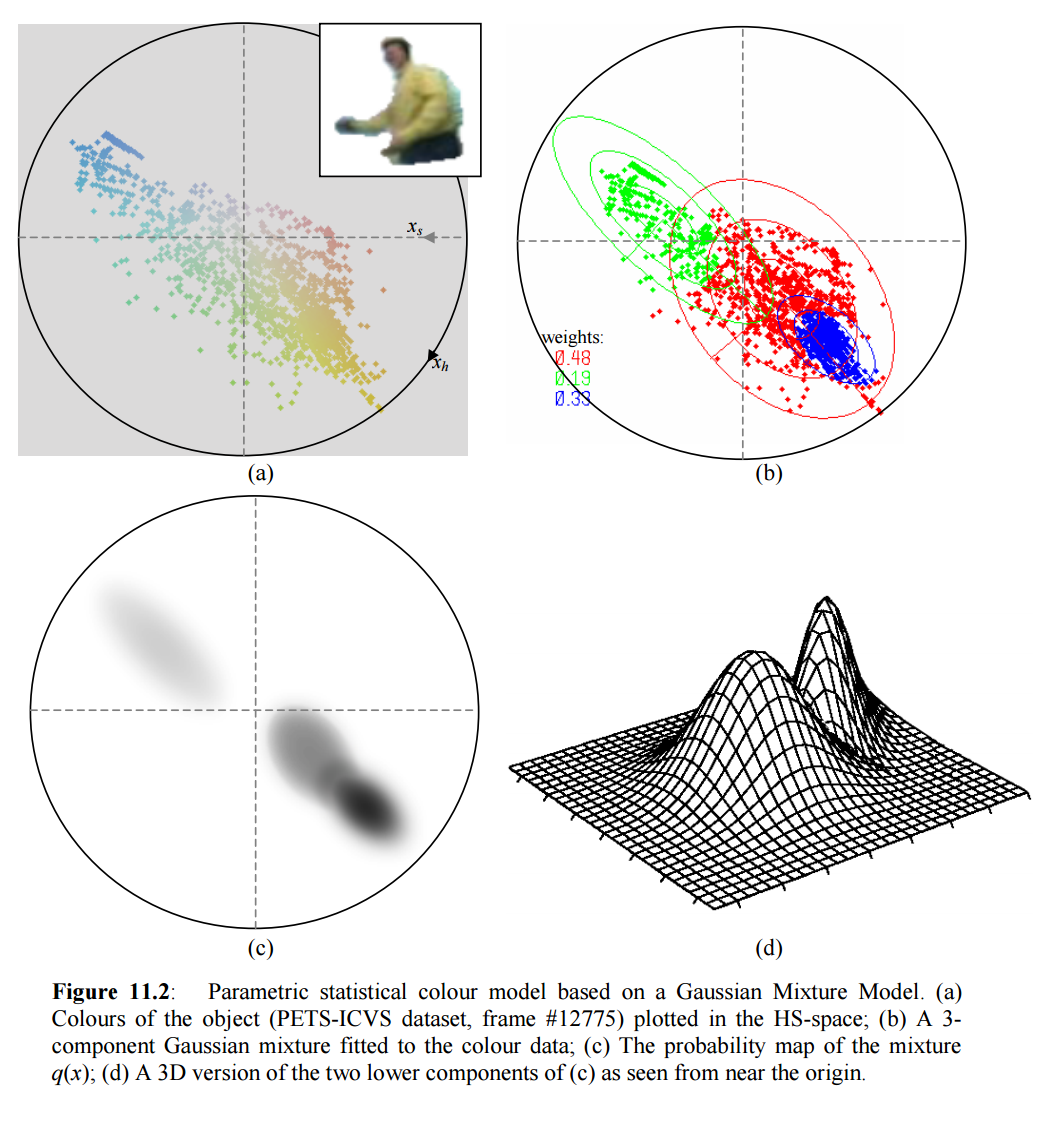

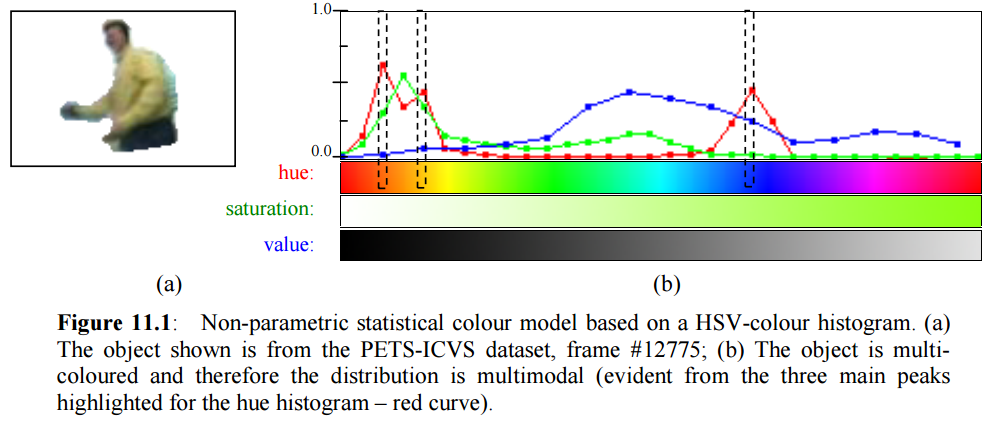

One complication that arises with colour-based tracking is that it is more common for objects to be multi-coloured. A person might wear different coloured trousers and shirt. How can we represent the colour of such a person? And how can such a colour model help us in successfully tracking people?

To answer these questions, I made use of the HSV colour space. HSV is more well-behaved than RGB and allows for handling hue (colour) separately from saturation and brightness. The figure below is a colour histogram of the person shown, with the dominant colours being dark-blue (trousers), yellow (his shirt), and orange-sort-of-colour (skin and face).

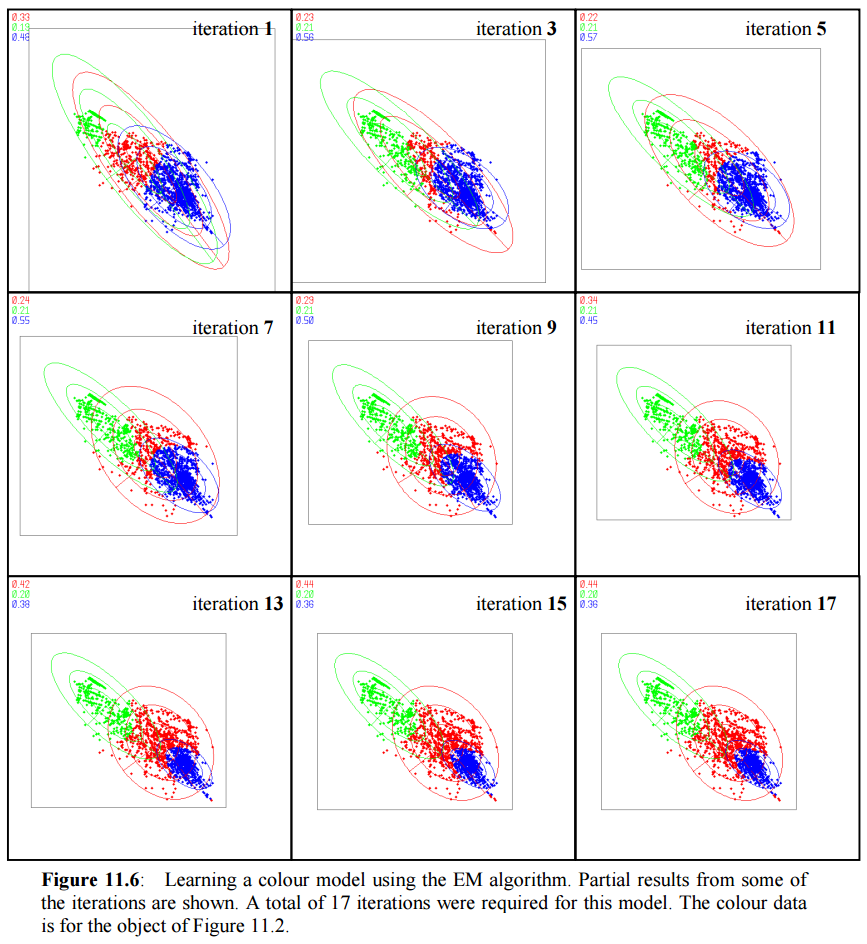

A Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) is used to represent a person’s colour model. This is shown below. Note the 3 dominant clusters representing the 3 main colours of this person. Each cluster is represented by a 2-dimensional Gaussian distribution in hue-stauration space and the 3 clusters are weighted according to their dominance — hence the term mixture of Gaussians.

Finally, in order to learn the GMM colour model of a person, the Expectation-Maximisation (EM) algorithm was used. This is a statistical method that can perform clustering and learn the parameters of the GMM automatically with little a priori information given. More details on object trackijng can be found in chapters 9 to 11.